an article i wrote from Hii Magazine Issue 1, peace 2 Spurge C. for the editing

They say someone is only truly gone when their name is spoken for the final time. What does this then mean for the many artists who’ve died years ago but “new records” and their likeness are being sold to us as if they are still here?

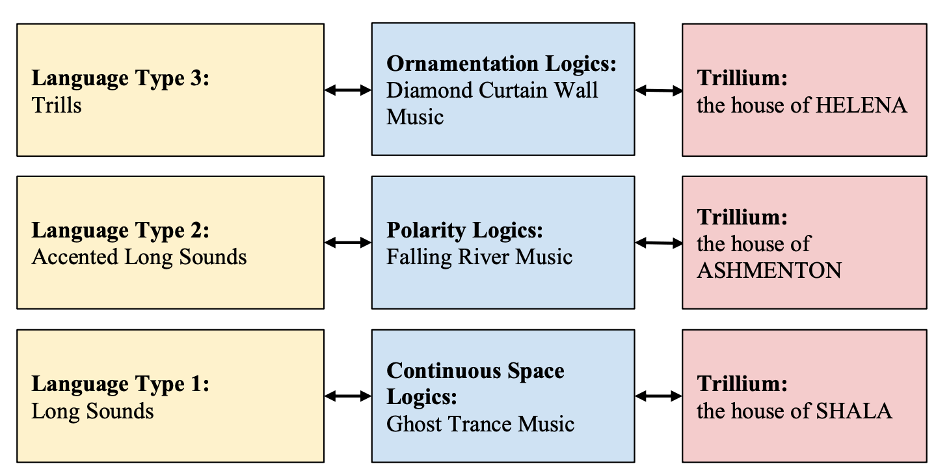

R. Murray Schafer, an acoustic ecologist, avant-garde composer, and proliferator of the term “soundscape”, who recently passed away in August of this year, created a term in reference to the expansion of radio and the accessibility of recordings. The concept came to be known as “Schizophonia”, or the splitting between the original sound and its electroacoustic reproduction. In his 1994 book, The Soundscape, he described his fraught neologism even further:

“We have split the sound from the maker of the sound. Sounds have been torn from their natural sockets and given an amplified and independent existence. Vocal sound, for instance, is no longer tied to a hole in the head but is free to issue from anywhere in the landscape”.

When he created this term in 1969, radio was already a market leader in how western civilization listened to and broadcasted sound. Before radio, the marketability of sound was like most other commodities, a physical product to obtain before enjoying. With radio beginning its reign on Christmas Eve 1906 from Ocean Bluff-Brant Rock, Massachusetts via the first amplitude modulated transmission of “O Holy Night”, the material bifurcation between sound and artist (already tearing as it was with vinyl before) now split completely; no longer carrying a corporeal value, but considered an modern atmospheric resource to mine for advertising dollars. Since becoming a renewable energy, in effect, how has the music industry further exploited this schizophonia to reap the benefits of the sound of artists no longer with us? What does it mean to hear the songs, or voice, of someone who may not have even wanted for us to listen?

One looking glass to peer into for a potential answer is the relation between Rap and radio. There are many golden ages with respect to radio but one of them was definitely late 20th to early 21st century; which occurred about the same time as the golden age of Hip-Hop in the early 90’s, soon giving way to Gangsta Rap of the late 90’s and the bling era of the early 2000’s. This moment is encapsulated by extravagant showcases of material wealth, McMansions on MTV Cribs, and a looming subprime mortgage crisis in the then near future. A little before the Napsters and Kazaas of the world put the music industry on notice to take evasive maneuvers, radio was where music lovers checked out the music they desired before buying. And they often did. Through DJ’s, like Funk Flex, who built anticipation as if it were a performance piece, stacked with reloads, explosion soundboard .wav files, and level peaking yells before playing the unreleased song in full. 100 years after “O Holy Night” transmitted along New England shores, radio became the main agent to accruing wealth for artists and label heads alike. This exponential expansion of Rap capital is still best understood and embodied through the music and (after)life of Tupac Shakur.

Shakur’s journey through the music industry is emblematic of how the late era capitalism’s meat grinder came to black cultures’ doorstep— enticing fame and fortune under the stipulation of total dominion of self, likeness, and voice. Since Shakur’s death (and the three albums released while he was alive), six albums totaling 147 more songs, have been released. Tupac’s cultural counterpoint, Notorious B.I.G, had his second studio album “Life After Death” released sixteen days after his death– thus beginning the undead rivalry between the two that continues to this day with docuseries and unreleased songs still stoking the flames of a long forgotten label war. Music labels have looked to this now decades-long example as a blueprint for extracting value out of the dead artist, as is shown with more recent passings like Juice WRLD, XXXTentacion, and Pop Smoke. This posthumous culture, particularly surrounding dead black men, has proven to be a massive success for the labels that signed these artists, with 2pac (as a brand, not as a man) reaching the Forbes’ Top 25 list thirty years after his passing. His paranoia of death often found in his lyrics has been recomposed by Universal Music Group to resemble a Nostradamus type beat– haunting lyrics of a tortured writer predicting his death years before with coded language found in his new unreleased batch of recordings, on sale now.

Such capitalistic hunger reverberating through voice detachment and exploitation existed well before the untimely death of Shakur in 1996, even spreading into sonic based imperialism. In 1970 at the height of the Vietnam War, the US employed “Operation Wandering Soul”, a psychoacoustic war tactic that hoped to tap into Vietnamese culture of belief and rituals of their deceased. Vietnamese culture often calls for a burial in the person’s homeland and if an improper burial takes place, then the wandering soul will venture aimlessly in suffering. U.S. sound engineers spent weeks altering voices into ghostly cries impersonating lost VietCong souls asking their countrymen to defect and cease fire. This mixtape, dubbed “Ghost Tape Number Ten”, was installed at military bases and attached to helicopters as psychological propaganda. (Source)

Another form of colonial abuse of non-western sound cultures lies in Australia, in the business relations of Australian settlers and the Indigenous Australian Peoples. Indigenous Australians have a deeply rooted structure in their grieving process of deceased loved ones. This structure, better known as avoidance practices, can span from averting the gaze of a member of a family whose loved one has recently deceased to not referring to a deceased individual by name, out of respect but also as it would be too emotional for the grieving family. Since the proliferation of media in the 20th century, this has extended into pictures, video, and audio of the individual captured. Many documentaries and Australian media often come with the disclaimer, “The program may contain images and voices of such people who have died”. During the initial settlement of Australia by Europeans, forms of Sorry Business, or a series of bereavement protocols noted in Indigenous Australian culture, had to be explicitly written into the law as there was an immediate refusal from Indigeous Austrailians to participate in any non-sorrow centered activities during the grieving period. Some examples are not addressing the day that a family member had passed on or not referring to the recently deceased owner of a business one might have been in dealings with prior to their passing. Although ratified by law, many of these practices were often disregarded or outright abused to further the extraction of land and resources many of the Indigenous Australian people used for their livelihoods. This neocolonial death marching theme has found itself from 17th century imperialism to our Spotify playlist.

Such avoidance practices are not absent in American culture either as we often hear posthumous grievances from surviving loved ones, if not from the musician themselves. Prince explicitly spoke to his own avoidance practice, demanding that no more records be released after his passing. This, of course, was not heeded as three “unreleased” albums have been released since. Tupac’s voice and life extended into projects and albums he had never probably imagined, featuring on tracks alongside Elton John, Dido, and Kendrick Lamar, the last of which “interviews” him on his 2014 sophomore record, To Pimp a Butterfly (working title once being To Pimp a Caterpillar (Tu.P.A.C)), 18 years after his death. Juice WRLD became a platinum selling artist after his passing. His body of work seems to be more valuable reanimated than alive. Although other genres are culpable, Rap and the industry that sells Rap seems to have a fascination, if not all out obsession, with these undead sounds. Because their child signed their likeness away, many grieving families often go through their own avoidance practices; hoping not to hear their child on the radio, an award show, movie trailer or in increasingly less extreme cases, a hologram performance.

But these examples are not the only pathways in which labels and families acknowledge the life and afterlife of an artist and their creative output. Jasmine Dumile, the wife of Daniel Dumile, better known as MF DOOM, announced the passing of her husband on New Years’ Eve in 2020 at the age of 49 with DOOM actually passing on Halloween months before. Public expression of a family member’s death months after provides close ones time and space to process without the trained eye of fans and media following those grieving at their lowest. In DOOM’s case, it only further perpetuated his irreverent preoccupations with anonymity, mythology, and subcultural subterfuge. What might be seen as an ever playful attitude towards the music industry since he donned the metal mask in the late 90’s was surely his way to ensure personal agency and control of one’s own life publicly and privately. This mindset with DOOM only continues in his wake. Records released since his passing have been in the single-digits with no talk of any future plans on the horizon. On track for a man who was oft-late to the party, if he decided to show up at all.

By introducing a waiting period after a death, a more ethical approach towards honoring one’s humanity (and voice, by extension) is possible through establishing clear boundaries of being for your favorite artist no longer with us. This practice could provide a means to rid ourselves from a culture of consumer entitlement even if the producer in question is dead. Such a practice can allow listeners to form a more material connection to what they’re hearing, where it came from, and its finality. The opposite path leads us to a life’s work condensed into a flattened object, designed for consumption. This framework introduces a neoliberal psychedelia around the work of an artist, purely churning itself out for the audience’s short-term attention span in hope that one more piece of “content” will make them forget they signed up for a 7-day trial period using their credit card. Perhaps it’s the embodiment of the streaming era where entertainment has pivoted to attrition cloaked as something worth our interest, but this road has taken us to a method of thought where it’s as if the listener can feel entitlement towards an artist in the afterlife. There is seldom a call for reflection on what it means for an industry to peddle “new material” from an artist who has been dead decades, never needing to come to grips that this voice is gone because in some ways, it isn’t. Or at least not yet.

Hearing your child’s voice years after their burial can be its own exhumation. Wandering souls fill up our playlists often without recognition, much less consent. In a way, these artists are very much still with us— releasing new albums or works not available on digital streaming platforms now announcing their release as if it’s a new product we haven’t had access to for decades. It starts to be hard to mock conspiracy theorists too hard when the thin space between reality and the parasocial relationships we construct with an artist both before and after their death is now virtually nonexistent. But for those that knew these people, these mere electroacoustic reproductions are filled with emotion, home video flashbacks, first times, last goodbyes. This Sorry Business with respect to the posthumous album is an unapologetic machine, chugging itself through the people and families of those who only wish rest for themselves and their loved ones.