an old writing that was originally shared in Baton Rouge’s Yes We Cannibal’s 2022 Zine . Not even sure how compatible this piece is with where my head is now but shout out to personal documentation

My thought for today is that Fred Moten is Ornette Coleman, or at least Moten is playing free jazz as often as he can when creating his works– those clearly defined as poetic or otherwise. In December of 1960, when Coleman recorded Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, what we heard was a two-quartet conversation with no preset key, perceived tonal system, or melody. Many at the time didn’t understand how this could be considered lyrical or that the headiest of jazz had reached its intellectual precipice with Coleman. That jazz left the body purely to reside in the brain. But to his ears, he was only playing the blues. Listening back to Free Jazz, if you think about melody in terms of reaching tonal catharsis or bounding within a chord structure, many “wrong notes” are being played as we’ve come to understand musical wrongness. If we were to even fall in line to such logic, Miles Davis already had a saying:

“It’s not the note you play that’s the wrong note – it’s the note you play afterwards that makes it right or wrong.”

Listening to Coleman, or Free Jazz in general, is now a much more widely understood area of the black music continuum. Very little conversation is ongoing whether it’s something to “get”. For someone who listens to Coleman, I’ve come to the personal understanding that it’s not about “getting” every musical idea but to feel to wholeness of it, or to enjoy passages as they come and the density of ideas aren’t necessarily designed to be understood (as we understand certain songs and their utility (as ear worms or recitation)). Not “getting” something might also be of the functioning points of Free Jazz as a concept, a music that cannot be captured wholly and is therefore as present as something must be since its near impossible to contain it within a jingle, traditional song structure, etc. Like the politics within and surrounding Free Jazz during the time of its current creation, you must approach this music on its terms or nothing at all. Once you cross that hurdle, there’s so much you realized you’ve let go of without realizing.

For Moten, the same process has finally come to me. As someone who has spent their entity of their understanding bounded within the conceptual regalia of STEM, stumbling on Fred Moten’s work was both a catharsis and a deterrent. Listening to him in lectures was such a joy and gave me so much enthusiasm to find a space within it, but once I read his written word, I imagined the black gatekeeper turning me away until my .pdf folder was this tall to ride. It was only until just a couple days a friend of mine spoke to me in a discord channel after watching late-night youtube reruns of Black Journal with me bringing up this downtrodden dilemma that she said something that cracked my whole understanding wide open: “oh, he said he likes it when sentences don’t make sense, that’s where reading begins with him”. I immediately thought of Coleman merely expressing his thought that he only playing the blues. Because he is! Really they both are. Moten, like Coleman and Free Jazz writ large, is in conversation with the black music tradition and what we’re hearing is one side of a very old (or non-linear) conversation. Moten has transmuted the feeling of free jazz into the English language. Bending notes, playing the “wrong chord”, atonalities, it’s all there. Even through his collaboration with Stefano Harvey, he’s only playing music and we’re reading the notation on the page. Probably another reason why people have often said his lectures “land” more than his books for so many.

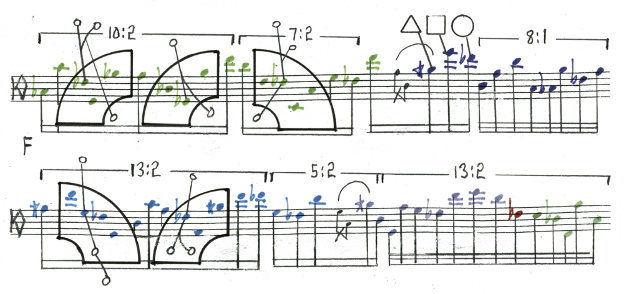

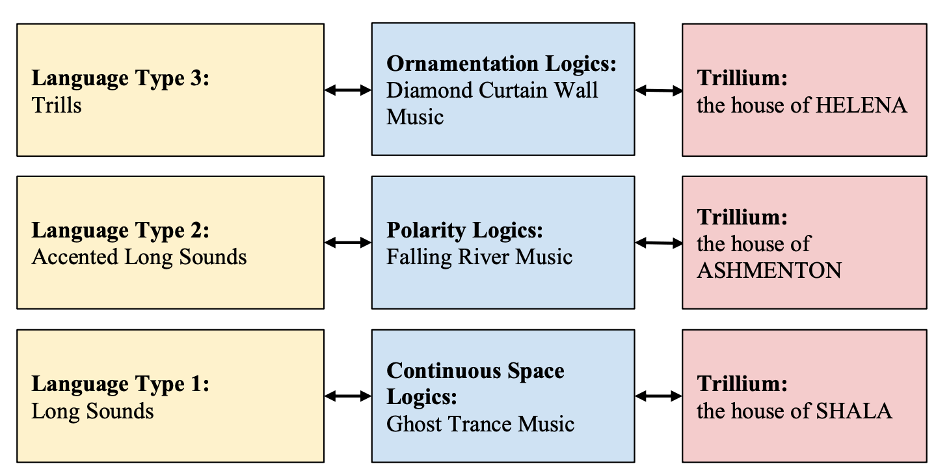

Another lens to peer this thought I’m floating through is finding a relation between the aleatory, the creative, and the meaning found for in different cultures. In music, the two minds that spring up are John Cage and Anthony Braxton. Cage has spoken at length about his connection with aleatory, or chance, music—notably in 4’33 with the chance variable being everything not on the page becoming the composition; the room ambience, cleared throats from the crowd, even the page turnings from the orchestra onstage (as the composition does follow a metered notation). Braxton has been on the otherside of this chance music and instead as prompted his own understanding of improvisatory musics under the moniker “creative music”, which he’s describes as an open, or language, music that give performers room, not chance, to include themselves in a composition, notated or otherwise. A linguistic analog between this dichotomy of music might be Moten’s possible jazz approach to the king’s English and William S. Burroughs popularized découpé or cut-up technique. The cut-up technique is also an aleatoric (albeit Dadaist in origin) process where written text is cut-up and rearranged forming a wholly new text. Speaking with another friend, they first assumed Moten was himself applying this method to his works, but personally I think it falls in line with Braxton and Coleman’s approach to their own relatively warped way of playing the standards: once again finding yourself in a conversation with tradition of feeling, but refractive enough to look completely different.

The connective tissues between musicality and language that both Ornette Coleman and Fred Moten seem to inhabit dematerialized the panoptic black gatekeeper for me. I stopped taking the density of his work so personal. Something about reading and finding frustration not exactly knowing what it is you’ve read is an almost preternatural response for so many. But we’ve gotten over this feeling and just decided to understand through feeling with Jazz and although I might be behind the bend with these thoughts, I’ve allowed myself to feel the words on the page the same way, even when it’s stamped as a critical text. Confusion doesn’t always have to be a bug, it can often be a feature to find where you reside within it. It’s all jazz.