here’s an interview I did with Kelela for a euro magazine back in february (edited):

Kelela (00:00): Hey, Ryan.

Ryan C. Clarke (00:01): Hey, Kelela.

K (00:49):

Yeah, thank you so much for making this happen. I’m so glad that you’re the person to do this. It’s perfect.

RC (00:57):

Yeah. I’m so excited, and I feel like we sometimes, somehow, orbit in similar capacities. So to finally make the time for a direct contact is exciting. I’m very happy. Thank you for making the time.

K (01:17): A pleasure.

RC (05:29):

I had to send these questions a couple days back, about a week ago. I was sent the album in advance. I listened to it last night and again this morning where now I have a completely different group of questions.

In the beginning you kind of get this dive in and then you start to hear the sound of water more explicitly, and a kind of bubbling back up reprises near the end if not the last song.

Much of the text of the record seems to deal with the ruptures that darkness can produce. Almost a potential, a possibility without surveillance. To be in the dark. A lot of this deals with nightlife and dancing, but those thoughts aren’t necessarily about what the music is saying. Not so much “pump up the jam” or a song strictly around an unrequited love, but a possible phenomenon that has potential to produce something new. And I was thinking about the Raven, but also the Phoenix having this idea of self-determined actualization.

K (07:37):

The record was going be called Phoenix before it was called Raven.

RC (07:40): Word <laugh>

K (07:41):

Phoenix is so played out. We can’t, I can’t.

[For the title track,] I wrote the lyric as Phoenix initially, because that’s what I’m talking about, is that experience. Topically this is a pretty dark album or it’s really like confronting something, and it feels heavier. But at the same time, it’s about like the liberation that follows the confrontation. It’s really about the release. It’s confronting and it is dealing head-on with some things. There’s a lot of boundary drawing.

There’s this delicious catharsis and a feeling of, I want to say triumphant, but that’s a little too conclusive. It’s more like we got through that. We made it through that. The implication is if we can get through that, we got this. That’s an ethos that I am wanting to champion and what you’re hearing at the end is like the sound of me coming out, you know?

RC (09:44):

Yeah. I kept writing down, “self-determination”, throughout so much of it. Through all this labor, I’m reborn. I am becoming by having to deconstruct your past self and all the systems that were imposed upon you to really start to rebuild a new sense of self.

For this record, how did you reconcile the weight of time between Take Me Apart in Raven, where in the interim you might’ve understood yourself to had become a new person or carried new sensibilities about who you wanted to be and how you want to portray that?

K (12:32):

There’s so much continuity. Since the beginning have never been like responding to the times or doing anything that’s like, feeling on trend. It’s just never felt like related to what’s going on around me.

There’s like a topical disadvantage in that, but I think the long-term advantage is timelessness or the feeling that it isn’t related. I feel like I could release any song of mine that I previously released at any point and it would feel like new music.

That gives me a lot of comfort in a continuity or thread that feels clear and good. Even though when I listen to Take Me Apart, there’s things that I’d be like, “hmm, I wish I could change that.” But generally, I’m feeling like they really match the fuck up, you feel me?

I think there’s something about leading with vulnerability and that kind of being the ethos since jump. Sonically, there’s nothing I really would shift or change from Take Me Apart to this… there’s definitely growth. It’s the beginning of the sentence and [Raven] is like the period.

I love a story that’s built over time. My project is to reveal that in this beautiful order that, that like makes sense as a narrative that also speaks to where we’re at. Not on trend, but responding to what is rather than what we, what everybody, wants to hear. What [feels] appropriate for this moment, for me, that’s like a big part of why I put the music out that I put out when I put it out.

RC (18:01):

I feel this kind of larger arc and there being arcs in the arc of how you’re playing with storytelling.

Most evident is this sense of longing, ideas of catharsis, release, or moments of transcendence. And then having to investigate what those perceived moments of transcendence might mean for your own emotional or relational health.

It’s like you’re a mirror looking back at a mirror, looking back at a mirror, looking back at a mirror to make sense of the interior while experiencing the exterior. In a more simple way, it’s like crying in the club, you know, like you’re having a beautiful time, but also like you’re going through some real shit.

K (19:14):

A hundred percent. There’s two ways that the club does its thing— one way is the escapist realm, and the other route is the one you’re talking about right now. The tears in the club framework and as an artist, one thing that I’m trying to do is for my contribution to help people confront what’s real.

[The] catharsis in that is I want to have to my songs in the club and you should wake up feeling better in the morning rather than, “I’m mad that that’s over and that I’m back at that real life.” It should be like, “the club helped me deal with my real life”.

There’s some of us who are using the club like that. There’s a devotion that’s coming from that place that’s giving church vibes. I would say that’s something that’s important to me… being like a sonic in a way that helps you get into what’s really going on rather than out of.

RC (21:38):

Yeah. It’s not an exit. Hopefully you’re entering something else. In that way, the question might become how I introduce people into a tradition or a better relation with this space where you might currently carry a poor relation to the club.

K (22:58):

Exactly. One of the other things that I can say I’ve done is my music feels seamlessliving inside and outside the club. I’m not trying to say I’m special or whatever, but it does feel like there’s a way that I do it that’s different. There’s a way that I make it for both. I also I don’t think that people are making vocal music for the club until very, very recently. That was the intention for me the entire time.

RC (24:25):

In the video for “Happy Ending”, it looked like you found an interest in making your connections to a larger community more explicit where you’re no longer a singular artist on stage but part of a collective. How did you make sense of that?

K (27:01):

Previously on Take Me Apart, I was more, interested in being a bridge and straddling two worlds, where now I feel like I am less interested in the bring in and more interested in serving the people who have always been front and center. Quite literally at the shows…never not getting a reference that I throw out. With queer black people, there’s nothing that I do that they don’t get because of the intersections. I want to serve and center those people but it’s not as simple making them be pleased sonically, you know what I mean? And thinking about them as me.

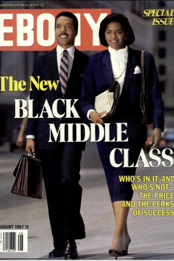

Part of how I came to understand the way that music is so racialized is in the way that we think about white sounds and how black music and blackness sounds has been usurped by everyone and just what that means for all of us. It’s something I’ve thought a lot about when I would be making music. I’d be trying to literally create a balance between having enough elements there for the heads to have their moment while

also having enough there for the vocal girls to also have their moment. [For my music] to feel like that was my dream because we never get both at the same time.

RC (31:00):

That’s very considerate of you. A tending to. “This is what I have for you. I hope you enjoy it”. Kind desire.

K (31:20):

Literally what it is. I feel like I was doing the most before. Like I said before how I was trying to straddle these two places, right now I’m just kind of like sitting where I was standing.

It feels way better and maybe the key to bring people in is sitting where you stand <laugh>. And then niggas just show up! I just felt the urge to try and in a way that’s like also low key uncomfortable. To be that feels like that’s a courageous point for me. If I’m being honest kind of, it’s kind of scary to not be trying to strike some sort of literal balance.

When I think about choruses for example, one of the things that I said was I’m going to use this project as a way to affirm myself. I didn’t know how it was going to sound, but I was like, we got to make that our process, at the very least, since I’m the boss bitch of this whole thing.

So why should I feel inadequate when it comes to my process or how I make things? I’ve never looked too hard at what other people are doing, obviously. I mean, that’s probably obvious, I definitely have felt the pressure from like within music business where capitalism and art intersect. People are starting to make songs that are shorter and have one word in the chorus as if you can’t have too many words in the verse.

It’s giving least common denominator and a pattern that’s gotten fiercer in the digital era. There’s cool innovations and things that can happen when people are working under that type of constraint so I’m not saying all of that is bad, but I am saying that there is something lost.

I’m not going to write with any other songwriters, official songwriters. I think I make cool music without other pop songwriters. There’s a way that whiteness and maleness and can breed some sort of inadequacy. Not enough around seeing of how we’re doing it, how we do it, how it just comes out. It oozes out of us, but that refinement comes from someone at someone else somewhere else and it’s usually a white body.

RC (36:22):

Using the word refine is pertinent. Thinking of how a refinery refines; there’s nothing like refined about refining something. It’s something that’s often violent, messy, and not asked for. To realize that you don’t have to agree to basically like larger systems of refinement, that you can reject that tradition where the trend lines are going with popular music. It’s tricky as what we’re talking about is about the catchy things that people do in music. So, the more you look at it the more insidious you really see these actions of making something catchy is. Almost something too extractive or too exploitative.

K (37:26):

These songwriters, they sit in the room, and they’ll just go through their phone all in their notes of all these like, catchphrase things that they heard people saying. You know what I mean?

RC (37:36):

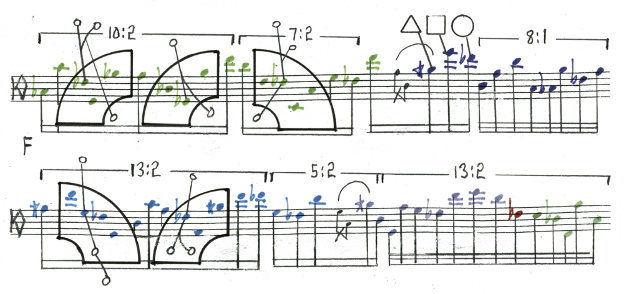

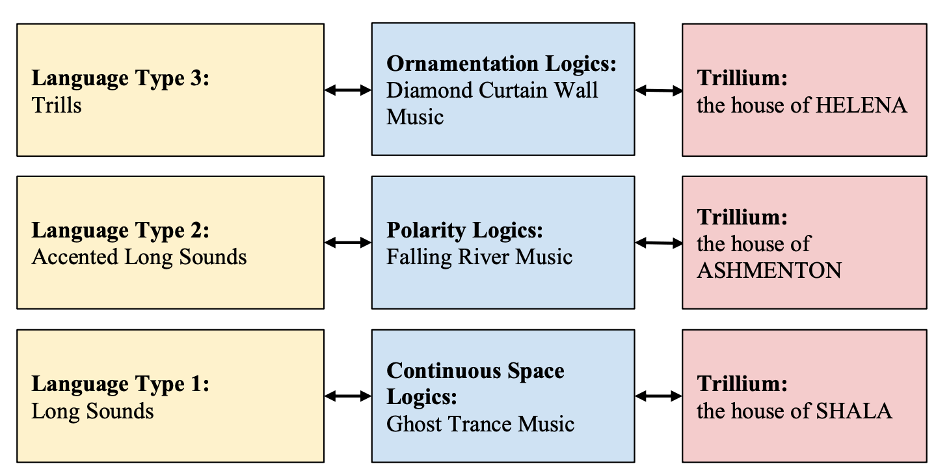

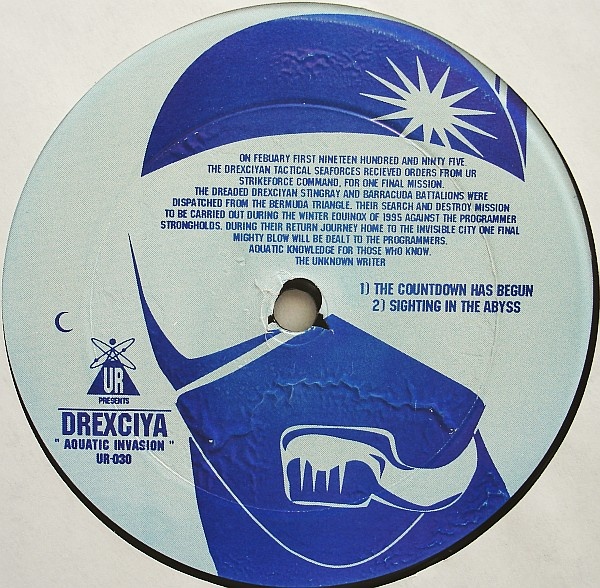

In refusal of that finds oneself in a different kind of continuum. After finishing the record it made me think of A Guy Called Gerald. Black Secret Technology or something in the hardcore continuum where it was produced with no interest in contributing to the characteristics of what a mainstream album wants to sound like. Not even what sounds like, but how it was made, like almost from like a material place.

K (38:26):

Can you tell me more about what you mean by that?

RC (38:36):

Raven seems to not be performing the gestures of how a popular song is supposed. For example, there are no chorus that literally sounds louder than the rest of the track for radio play or the chords aren’t resolving in ways that feel overly familiar or it’s not mixed with a certain brightness. It’s clearly not interested in that. And I can understand people feeling like the mix doesn’t sound right and it might be a little muddy, but it might be trying to do something different? It might be trying to engage with a different tradition that to me sounds more like what a lot of UK or Detroit techno people were doing and how they were making another aesthetic.

K (39:32):

There is a dirtiness. We’re definitely in a digital hi-fi moment. It’s just not the only place that I situate sonically. There’s a little bit of that on this record but there’s an analog approach to digital music. It doesn’t feel committed to the current dominant sonic aesthetic that people really feel drawn to.

Me and my girlfriend sometimes we have this relationship when you are in a period where you’re wearing your hair straight for a long period and even though it’s really cool and fun to play with you feel like you start to rely on it. Almost like you don’t feel good with your natural self. So we just stop it.

Soon as I feel like I can’t not do that thing, if it’s like wearing makeup or anything that like brings us closer to desirability as if I can’t appear without it, I sort of just practice pulling away from it a little bit. And I would say that this is how I treated this record was kind of that for myself. If I thought I was feeling an insecurity what it sounds naturally come out of me, I think is something I need to really get into and confront that.

RC (42:02):

What I’m thinking of is self-possession.

K (42:07):

I’ve never used that term. How do you think about that?

RC (42:16):

Choosing yourself, embodying yourself. Not getting so hyper-vigilant or becoming your own surveillance.

K (42:35):

Exactly. The messaging in this music will only be as powerful as it transforms me. If I make this a rich experience for myself, then it will spill over somehow. I know it’s not a direct or literal act but will be colored by that and that’s what people will inadvertently get.

In a way the intention [of this record] was less around the specific meaning like what this record is about, but that I want this to help me heal my relationship with perfectionism which is really white supremacy.

RC (47:24):

I like the idea that you have a desire to signal both inwards and outwards to that kind of self- determination, affirmation, and possession as path to connect with your people. Fred Moten calls it, the consent to not be a single being and I think that that definitely happens in the club. Like music, we can also use the environment of the club to like really to start to gesture at those ideas. We can form a collectively distributed mind where we’re all interested in like possessing ourselves. Not each other because we’re not owning each other, but in the way that we truly believe in like each other’s actualization. That can build its own thing.

K (48:59):

With “Washed Away”, what I kept saying to my creative director is I feel like a fairy who’s like descending upon the story and being the narrator. She’s back descending upon the land to tell you the beginning of the story. [My friend] said it sounds like, “you niggas are worthy”.

That is literally what that song and what this record is meant to do. It’s really meant to center black queer people who have been clear about their marginalization and have been facing it with vulnerability to still wear their heart on their sleeves with that type of commitment to love. That’s a labor that black femme and non-binary people have been doing for so long. It’s something that I’m wanting to affirm.

RC (51:21):

These ideas begin to feel beyond the sound of the music where there’s articulated effort in the gesture of care. This is why I get frustrated about reviews since you’re merely in dealing with the taste of the thing where the core idea that this was shared for this intention to help someone on whether or not they can even fight for their own potential. That notion is more important than “I didn’t like the drums.”

K (52:20):

At the same time, it’s like also an invitation to engage why you don’t like the drums! There’s way certain systems guide so much of how people assess. Especially in journalism and the sort of pick me culture of like white adjacency.

RC (54:48):

Yeah. Well, they want you to kiss the ring and you’re not doing that.

K (54:52): <laugh> period.

RC (54:54):

Such a good conversation. It’s been such a pleasure. Thank you.

K (57:02):

So much Ryan. Really appreciate you and your time.

RC (57:05):

Same to you, same to you. Be well be easy and have a great afternoon.

K (57:12): Bye.

RC (57:14): Bye.